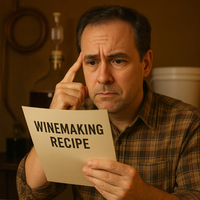

The Hidden Dangers of Recipes in Winemaking: A Comprehensive Guide

Posted by Matteo Lahm on 21st Dec 2024

So, you've got your fruit, your yeast, your carboy, and a recipe you found online that promises to deliver the perfect bottle of homemade vino. But before you start crushing those grapes (or apples, or blueberries), let's take a moment to discuss the potential pitfalls of following a winemaking recipe to the letter.

You see, the problem with some of these recipes is that they might not take into account the natural variability of fruit. If they don't, continue with caution. Sure, an apple is an apple and a blueberry is a blueberry, but not all apples and blueberries are created equal. Depending on a multitude of factors, including the variety, ripeness, and growing conditions, the acidity and sugar content of these fruits can vary significantly enough to all but guarantee that your wine is doomed before you even begin.

Take apples, for instance. An apple can vary a full point on the pH scale. That might seem insignificant, but in the world of winemaking, it translates into a tenfold difference in acid levels. Remember that the pH scale is logarithmic. Every point is 10 times higher than the previous.

If your recipe calls for acid blend additions for a fruit that starts at a 4.0 to get it to a 3.5, and what you're actually using is a 5.0, you'll have only added a fraction of the amount of acid blend you actually need. That's like trying to fill a swimming pool with a garden hose! Worse yet, wine yeasts need a very specific pH range to function properly. If your pH is outside this range you will end up with all kinds of weird flavors and aromas that will render your wine undrinkable.

And let's not forget about sugar content. A blueberry, depending on its ripeness, can range between 8 and 18 Brix. Brix is a measure of the sugar content in an aqueous solution, and in winemaking, it's crucial for determining the potential alcohol content of your wine. If you added sugar based on a recipe written for a fruit with 12 Brix, you could end up with a must (the mixture of juice, skins, seeds, and stems) that is over 30 Brix. There's no known wine yeast that can ferment dry with sugar levels that high. You'd be setting yourself up for a fermentation failure, resulting in a wine that's too sweet and unbalanced. And if that were not enough, any solution that goes beyond the ABV threshold of yeast will cause yeast stress and before they die, they will produce hydrogen sulfide and make your wine smell like a bucket full of rotten eggs.

But what happens if your wine is too low in acidity and sugars? You end up with a flabby, lifeless wine that lacks structure and complexity. Worse yet, it's likely to spoil before you even get a chance to bottle it. Mold and other spoilage organisms thrive in low-acid and low alcohol environments, so a low-acid wine with a low ABV is a ticking time bomb of spoilage. Even sulfites will not protect a wine adequately with acidity and alcohol levels that are too low. The lower the acidity the more SO2 you need and there is a threshold for how much you can use if you don't want your wine to taste like burnt matches. There are instances where even commercial wines are recalled because of high pH and insufficient SO2 levels.

On the other hand, if your acidity is too high, your wine will be so sour it'll make you pucker. In this case, you can always back sweeten but if you like a dry wine, anything with a pH lower than 3.0 will be too sour to drink. It's all about balance, and achieving that balance requires careful measurement and adjustment of your must's pH and Brix levels.

When you get into recipes that call for water additions, you add a whole other level of complexity and potential problems. Water is by and large pH neutral. If your recipe says get X pounds of fruit and Y gallons of water to make a 6 gallon batch, you are doing the equivalent of driving on a highway with a blindfold. If you do not know what your starting point is, or you are not measuring as you go, water will take a bad situation and probably make it worse.

So, what's a budding winemaker to do? Treat your recipes as guidelines, not gospel. Learn how to test and modify both pH and Brix to get to the desired amount. Invest in a good hydrometer and acid test kit. If you really want to do it right, get a pH meter. These tools are your best friends in the winemaking process. They'll help you navigate the wild world of fruit fermentation and ensure you end up with a wine that's not only drinkable but enjoyable. They will also save you money. A pH meter costs less than losing 50 lbs of fruit.

The only recipes you can trust are ones that call for pasteurized fruit juices as a base because they are consistent in both sugars and acidity. But if you're going to evolve beyond them and make wine using fruit, you will need to account for the variables outlined in this article. Remember, no recipe can substitute for careful measurement and adjustment.

Nature is a mind bogglingly wondrous place filled with variation that defies the imagination. No two snowflakes are the same. Every single berry or fruit is unique. Recipe books are a great reference but, would you drive your car over a bridge made with guesses and estimates? You would not. This is not just about drinking good wine either. Bacterial infection is a real issue and you do not want to risk filling your glass with something that not only tastes bad but might even sour your stomach.

Measure twice, ferment once and drink happily. Good luck!