Should Sugar Levels Determine My Winemaking Process?

Posted by Matteo Lahm on 26th Sep 2024

Every harvest is like a box of chocolates—you never know what you're gonna get. Even grapes from the same vineyard can surprise you year after year. Weather cycles, temperatures, and a myriad of other factors play a significant role in how grapes grow and mature. Before you dive headfirst into the fermentation process, it's crucial to understand the characteristics of your fruit. Remember, your fruit should dictate how you make your wine, not the other way around. And the most important variable? Sugar levels.

Good wine grapes typically range between 23 and 27 brix, but let's face it, we don't live in a perfect world. Sugar levels can sometimes fall below 23 brix, and that's when things get interesting. In this article, we'll explore fermentation practices for both ends of the sugar spectrum and learn just how much it can and should alter your process.

High Sugar Levels: The Sweet Side of Fermentation

Grapes on the high end of the sugar spectrum will give you a wine that's about 14% ABV or even a bit more. At these levels, there's absolutely no need to add sugars. However, high sugar levels will push the yeast to their alcohol tolerance thresholds, and that can be dangerous. So, if you have grapes high in sugars, you might want to use a yeast starter to increase your yeast population and definitely use nutrient. The higher the sugar, the more yeast organisms you'll need to ferment dry. Yeast activity decreases as alcohol levels increase. This is where the nutrient plays a vital role. They provide your yeast with the necessary tools to keep trudging along until your wine has thoroughly fermented.

You should also should delay transfer to secondary fermentation. Transferring higher alcohol wines too soon could result in more residual sugar, and a slightly sweet Cabernet Sauvignon is not desirable. If you transfer off the lees too soon, you lower the yeast population. At the very end of fermentation, there is safety in numbers. High alcohol wines have the highest risk of stuck fermentation at the finish line. The yeast cells are tired and they need help from each other to get the job done. Also, lowering your population could result in stress that will cause the yeast to produce off flavors and aromas.

If you're fermenting a red wine, there are additional advantages to longer skin exposure. This will up the tannins and help balance the alcohol levels. You'd be surprised how much a few extra days can make a difference. The most tannin extraction happens at higher alcohol levels because alcohol is a solvent. If your fermenter has a snap lid and an airlock port, you can close up your batch at about 1.020 SG. If not, another technique is to wait until your hydrometer reading gets to 1.000. Spray a plastic bag with sanitizer. Cover your fermenter and shrink wrap it. At that point, fermentation has slowed enough where CO2 release will not cause an issue if there is no airlock. Any excess gasses will ventilate under the plastic and if it is not disturbed, there is no risk of oxidation. You just have to leave it alone until you transfer to secondary. The CO2 will lay on top of your must because it is heavier than O2. This will protect your wine.

Low Sugar Levels: Uncertain Terrain

Now, let's talk about the other end of the spectrum—low sugar levels. If your fruit is low in sugar, things get a bit more complicated. You might be tempted to add sugar but hold your horses! There are a few things you need to know before you start dumping bags of it into your must.

The 20% Rule

Sugar additions can be tricky business, especially when you cross a certain threshold. While acidity additions are apples to apples, sugars are not. Regardless of your sugar levels, you should aim for an acidity of between 3.3 and 3.6 for optimum yeast performance. But with table sugar, you should not increase your levels by more than 20% of total fermentable sugar. Table sugar has a different chemical structure than the sugars found in fruit. While table sugar contains 100% fermentable sugar, its chemical structure forces the yeast to behave differently because they have to break the sugars down from sucrose to fructose and glucose.

As a result, wines that have too much additional sugar added tend to taste hot because all the sugar additions do is facilitate more alcohol. The natural sugars in grapes contribute to flavors and aromas that won't be present with added sugars. So, stick to the 20% rule and adjust your fermentation process accordingly.

Also, if you are going to add table sugar, it is best to dissolve it first. Adding sugar in solid form makes accurate hydrometer readings difficult.

Rules Have Exceptions

You can use grape concentrates to exceed 20%. While you can easily use them exclusively as an alternative to table sugar, there are a few things to consider. They are more expensive and if you use enough, they can alter the flavor profile. They will also impact acidity. White and Red grape concentrates are 68 brix and contain fruit acid. They have the same composition as grapes minus the water. It is best to add them first to reach your desired sugar levels and then make additional acidity adjustments if necessary. Beyond that, grape concentrates are a good option that come with additional benefits. Since they contain natural grape sugars and not sucrose, you will not lose mouthfeel and body, which can happen with table sugar.

Light-Bodied Wines

If your fruit only has enough sugar to get to a 9-10% ABV, you can push it to about 12%. But just to complicate things even more, you wouldn't treat a 12% wine with no sugar additions the same as one increased by 20%. A grape that will result in a 12% ABV wine with its own sugar is a light-bodied wine, so you might want to pull it off the skins early to limit the tannins. Lighter body wines can be too astringent when they're too tannic. Lower alcohol levels are less likely to result in stuck fermentation because it is far from the alcohol threshold. Transferring it off the lees early is not problematic.

However, if you've added sugar, and it is a wine fermented on skins, you might want to prolong the skin exposure. Those added sugars won't result in the same flavors or aromas as the sugars in the grapes. It will be a bit more tannic but you will also extract more fruit flavor. That can help balance things out.

You also may not want to use a yeast starter in a low alcohol wine and manipulate your temperatures for a slower and gentler ferment. Longer and less combustive fermentation retains more esters and terpenes. Fermentation is a kind of boiling process and the more volatile the activity, the more CO2 is produced. As it bubbles out, it takes other compounds out with it. If you have to push the 20% rule to the limit, do whatever you can to accentuate other characteristics as much as possible.

Cold Soaking

Another technique to consider is cold soaking. If you can refrigerate your must, you can extract a lot more fruit flavor prior to fermentation. Cold soaking should be done between 33 and 39 degrees F. The colder your temps, the longer they can soak, up to a week. With warmer temps, do not cold soak for longer than one to two days. And you should sulfite your must beforehand if you intend to ferment with commercial yeast. You don't want natural yeasts to start multiplying. They won't get very far at low temps, but it's best to keep them on a leash regardless.

Cold soaking can be done with both high and low sugar musts. Fruit characteristics are beneficial in either scenario, but you would be employing the technique for different reasons and results.

The Science Behind Sugar Types

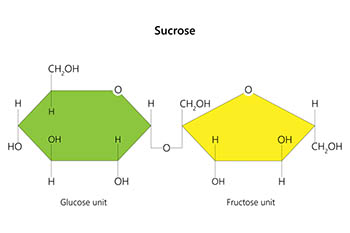

Let's break Sucrose, Fructose and Glucose down in simpler terms. Imagine glucose and fructose as two different types of building blocks. Glucose is like a square block, and fructose is like a triangle block. When these two blocks come together, they form a new, bigger block called sucrose.

In more scientific terms, glucose and fructose are single sugar molecules (monosaccharides) with the same chemical formula (C6H12O6), but they have different shapes. When they combine, they do so through a process called a condensation reaction. This reaction removes a small part from each sugar (a water molecule, H2O) and links them together, forming a double sugar molecule (disaccharide) known as sucrose (C12H22O11). So, sucrose is essentially a combination of one glucose and one fructose molecule stuck together.

This helps you visualize how the natural sugars present in grapes have a different chemical structure compared to pure sucrose found in granulated sugar, and this difference can indeed result in different flavors when fermented.

Glucose and Fructose (Grapes)

- Fermentation Rate: Glucose is generally fermented more quickly by yeast compared to fructose.

- Flavor Profile: The balance of glucose and fructose can influence the sweetness of the grapes and overall flavor profile of the wine. Fructose tends to be sweeter than glucose, so wines made from grapes with higher fructose content may taste sweeter prior to your ferment.

- Byproducts: The fermentation of these sugars can produce a range of byproducts, including esters, higher alcohols, and acids, which contribute to the complexity and aroma of the wine.

Sucrose (Granulated Sugar)

- Fermentation Rate: Sucrose must first be broken down into glucose and fructose by the enzyme invertase, which is produced by yeast. This can slightly delay the fermentation process.

- Flavor Profile: While sucrose itself doesn't directly contribute to the flavor, the resulting glucose and fructose will ferment similarly to the natural sugars in grapes. However, the initial presence of sucrose can sometimes lead to a different balance of byproducts, potentially resulting in a less complex flavor profile compared to wines made from grape sugars.

- Byproducts: The breakdown and fermentation of sucrose can also produce esters and other compounds, but the overall complexity might be different due to the initial composition of the sugar.

Conclusion: Let the Grapes Guide You

It's important to allow the grapes to dictate your process. Fruit is variable from year to year, and winemakers should be adaptable to those changes. In the end, you want a balanced wine. All the elements need to work together harmoniously for a good result. This approach not only will help you make better wine, but it will also be a gateway to learning new techniques. After all is said and done, you want to enjoy drinking what's in the bottle. It's better to have a lower alcohol wine with a balanced flavor profile than a beverage that tastes like weak wine mixed with vodka.

So, next time you're faced with a batch of grapes that aren't quite up to snuff, remember these tips and tricks. Your future self (and your taste buds) will thank you!